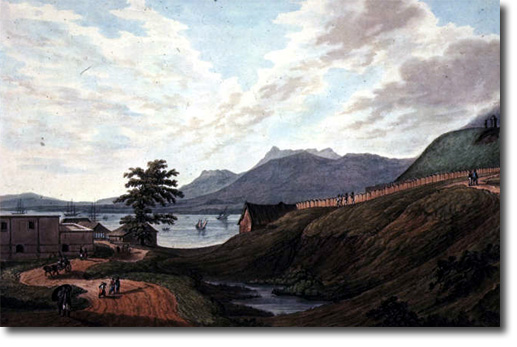

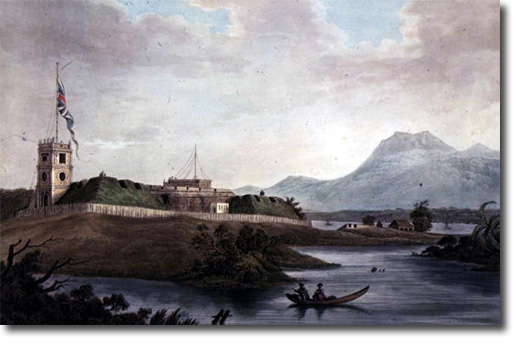

For a time, Bencoolen was a Presidency in its own right, and controlled the administration of other British factories along the West coast of Sumatra. As it was far away from the primary regional trade routes however, Bencoolen functioned mainly as a penal colony - it could not successfully produce pepper as planned and it became a financial loss to the EIC. Despite this chequered history, Bencoolen was in fact the last territory in Indonesia to be held by the British.

British expansion throughout South East Asia in the latter part of the 18th century began to focus on the Malacca Straits. In 1765, Captain Francis Light of the British EIC was tasked with establishing better trade relations in South East Asia. Light was posted to North-West Sumatra, where he quickly attained an influential position with the Sultan of Kedah. From 1771, he was involved in various proposals to cede portions of the Sultan's land to the British.

In 1786, Light reported to the Bengal Government that he had persuaded the Sultan to cede the Island of Penang to the British EIC for $6,000 a year. The offer was accepted - Light was appointed the first Superintendent of the new British colony, and became the colony's principal merchant.

By 1791, the Sultan of Kedah found that his revenues were being seriously diminished by the growing prosperity of Penang - he demanded additional income to compensate for this loss and made preparations to seize the island. Light obtained reinforcements from Bengal, and captured the Sultan's fort. The Sultan sued for peace and a treaty was agreed - the Sultan was granted an annual payment of $6,000, on the condition that the English could continue in possession of Penang.

Following the outbreak of the French War with England in February 1793, and the threat that this posed to English trade in the East, Light called for the reinforcement of troops in Indian waters. He also set about rebuilding Penang's defences. Naval reinforcements arrived in Madras at the end of 1793. Francis Light died from malaria on 21 October 1794.

In 1791 the subsidy was changed to $6,000, in perpetuity - for some years later this was raised to $10,000. This final addition was made when Province Wellesley was purchased by the East India Company for $2,000 in 1798.

In 1796, Penang was made a penal settlement, and 700 convicts were transferred there from the Andaman Islands. In 1805, Penang was made a separate presidency (equal in stature with Bombay and Madras); and in 1819, Britain sent Sir William Raffles to establish a trading post on Singapore Island. In 1824, the Dutch signed a treaty which surrendered their possessions on the Malay Peninsula to the British.

When administration of Penang was incorporated with Singapore and Malacca in 1826, it continued to be the seat of British government in South East Asia. Penang was reduced from the rank of a presidency in 1829, and eight years later, the town of Singapore was made the capital of the Straits Settlements.

The dollar was the currency of British colony of Bencoolen (also known as Fort Marlborough), and was equal in value to the Spanish dollar. Each dollar was subdivided into four suku, each suku then divided into 100 keping. After the Dutch took over control of Sumatra from the British in 1824, the dollar was replaced by the Netherlands Indies Gulden.

The proof copper coins for British Sumatra were presumably struck by the Soho Mint for the British Administrator at Bencoolen prior to the settlement at Penang being confirmed in June, 1786.

Generally available information is that in 1787, Matthew Boulton of the Soho Manufactory won a contract to strike coins for the East India Company's territory of Bencoolen on the island of Sumatra. It was the encouragement they received from the success of this venture that the Boulton, Watt & Son company began to actively develop minting equipment and the revolutionary mass production techniques that so transformed the production of coinage around the world.

Although the sheet copper and round blanks for the Bencoolen coinage were prepared at the Soho Manufactory, the coins were not actually struck there. The actual production occurred at a makeshift mint Boulton and John Scale set up in a warehouse at the French Ordinary Court in London1.

The Privy Council (which authorized the East India coinage), allowed just £200 for the purchase of up to three manual screw presses, which was incidentally a fraction of what it would eventually cost for Boulton to set up the Soho Mint's steam-powered equipment.

At the same time as the coinage for Bencoolen was being struck, a range of copper and silver coins were also being produced for the new settlement at Penang. The (Spanish) dollar was used as the basis of the currency used at Penang between 1786 and 1826, and was subdivided into 100 cents (pice). These coins also featured the British EIC balemark on the obverse, with the legend in Persian script on the reverse. In 1826, the Indian rupee was declared legal tender in Penang.

To the degree that the copper coins of Bencoolen pre-date the coinage struck by the British for use at Penang, they are an excellent record of the early efforts of the British to gain a toe-hold in the lucrative spice and opium trade of South East Asia.

As the very first coins struck by Matthew Boulton – indisputably the father of industrialized coinage, the copper coins of Bencoolen are of further importance to collectors of British and British colonial coinage.

0 comments:

Post a Comment